Stüssy / J Dilla / Stones Throw

02 / 11 / 2010

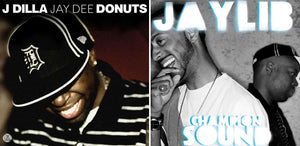

To celebrate the life of brilliant hip hop producer and rapper James "J Dilla" Yancey, we released a special limited edition tee shirt produced in conjunction with Stones Throw and the Dilla Estate. The shirt features Raph Rashid's classic photo of Dilla from the book, Behind The Beat. For the release we produced a three part documentary series focusing on J Dilla's life in Los Angeles. The Stussy x Stones Throw J Dilla Tee was released in February 2010.